The pastoral vocation is in deep crisis. A deep, deep crisis.

There are no doubts about this for anyone paying attention. Patterns of sexual abuse and narcissism and issues of physical and emotional health are painfully common.

Because I’ve been in this work for 15 years and because I have served in a lead pastor role for nearly the last 4, I’ve been giving lots and lots of thought to the basic question, “What is a pastor?”

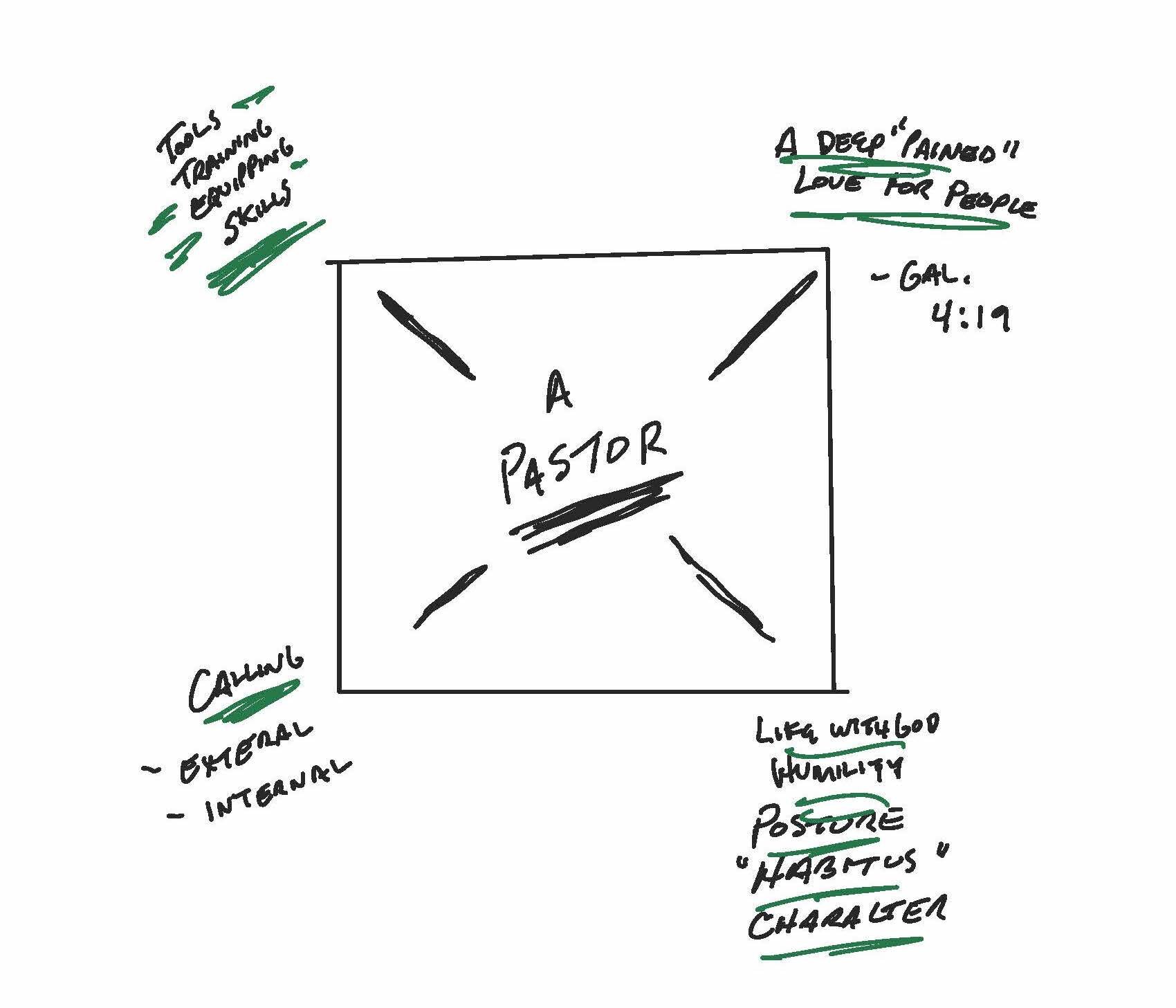

For now, I’m proposing the four-part model above. I’ll explain these components, in no particular order.

1. Tools, training, ministerial skills, etc.

We engage in formal training for this piece of pastoral preparation. It is only a piece, however. Strangely, some believe that the M.Div makes the pastor. It does not. This actually seems laughable to me now that I’m doing the work.

However, formal training is absolutely essential. At least, this is my very strong opinion. Formal training enhances ministry, it clarifies gifts, and it can provide a foundation for future fruitfulness. I’m an enormous advocate of formal training, especially at Beeson Divinity School.

Seminary training, or its equivalent, gives a set of tools, it cultivates the skill of thinking theologically, it gives the lay-of-the-land with regard to important debates, it helps the student see the contours of an issue so that the student learns to ask the right questions. Formal training invites a student into the conversation, the Great Conversation of the Great Tradition that has occurred for over 2,000 years.

But, seminary training’s ability to make a pastor is tremendously limited. One hears often, in a tone of frustration, “Well, seminary didn’t teach me this.”

But, that’s okay.

Seminary isn’t supposed to teach you that.

Formal training is essential, but it is limited. Something more is necessary.

A pastor is also more than a person who is “good” at certain ministerial skills. A pastor must be something more than someone who is good at preaching and who wants to be in front of people. Being good at preaching, and having a holy desire to lead, is very helpful. But a pastor is more than a person possessing at certain skill set.

There must be something more.

2. A deep, “pained” love for people.

In Galatians 4, the Apostle Paul says that it was like he was in the pains of childbirth. That is how bad he wanted to see Jesus formed in the Galatians (Galatians 4:19). He loved them and wanted them to know Jesus with such intensity that it physically hurt.

Though I have never been in the agony childbirth, I have seen the task up close and quite personal. This makes Paul’s image ring with power in my heart.

Until the would-be pastor experiences a deep pain, a deep inexplicable longing for something more for particular people, I’m inclined to think that we are not quite dealing with a pastor yet.

3. Calling: External and Internal.

I believe that an internal calling is essential. I believe it provides a unique fuel for the soul in the hardships of pastoral work. I also believe that an internal call has to travel with an external one. An external call, from an identifiable church community, inviting you to the work is equally essential.

In my opinion, until someone besides you has asked you, commissioned you, called you, or affirmed your sense of calling, you might not be a pastor.

Normally, these two kinds of callings work together in a beautiful way.

Maybe it is like this. Someone feels an urge for the work. That gnawing desire is expressed to church leaders and it is met with investment and encouragement (and a lot of redirection if necessary). It is affirmed over time. These external promptings fan into leaping flames the internal fire that burns inside.

(Something like this is the logic behind ordination, for what it is worth.)

Or, quite often, existing church leaders observe something in someone. Things that they cannot see alone. They begin to push and develop and encourage. Eventually, these external calls are yielded to, even reluctantly. From that point, the internal urges begin to follow suit.

In my experience, this is how calling works. There is an obvious implication here: seasons of waiting will be an essential piece of preparation for pastoral work.

4. Life with God, attentiveness to God, humility, posture, character, etc.

Unfortunately, it is not obvious, so I’ll say it. A pastor is a person who lives a life before God’s presence. A pastor is a person who seeks to cultivate, with thoughtfulness, the soil of the heart, that fruits of the Spirit might grow. A pastor is a person who is seeking to decrease that Christ might increase. A pastor is a person who endures spiritual embattlement with faith in Jesus, instead of fear (or, is trying to do this).

A pastor is a person who is gentle with people, even when telling them hard things. A pastor is a person whose personal godliness becomes the basis of all of the other ministry activities.

A pastor is a person growing in love for God and God’s word and who takes those loves and brings them into conversation with a deep love for God’s people.

As others have pointed out, the work of the pastor is a habitus— “ingrained skills, habits, and dispositions.” It is a way of living and being in the world that is a combination of character, skill, and attentiveness.

It is worth noting, as an aside, that this kind of life, posture, and character is mostly cultivated through suffering, trial, and trouble. Endurance, therefore, becomes an essential pastoral task.

———

There are other helpful models for how to think about the person of the pastor and the work of the pastor. I’m indebted to many folks who have gone before.

But, these are the things rattling around in my mind, that I share for your consideration. I would love to interact with you around these ideas, and if you are an aspiring pastor, I would love to invite you into a conversation about “how you are coming along” with regard to these things.